tl;dr: Everything I wanted to know, but was afraid to ask about elliptic curves.

$$ \def\ecid{\mathcal{O}} $$

History

Preliminaries

- finite fields $\Fq$ of prime order $q$

- $e_*$ is the multiplicative identity element in $K$, typically denoted by 1

- $e_+$ is the additive identity element in $K$, typically denoted by 0

- the smallest $n>0$, such that $\underbrace{e_* + e_* + \cdots + e_*}_{n\ \text{times}} = e_+$ is called the field characteristic.

- TODO: (full?) algebraic closure of a finite field $K$

- Example: for $\mathbb{Q}$, the full algebraic closure $\bar{\mathbb{Q}}$ includes $\sqrt{-2}$.

- TODO: Clarify the difference between $K$ and $\bar{K}$ (the algebraic closure of $K$), because points on the curve come from the latter.

- Wicher said it’s kind of like the real numbers: not every polynomial has a root in $\mathbb{R}$, so the algebraic closure of $\mathbb{R}$ are the complex numbers $\mathbb{C}$, where every polynomial has a root.

- Somehow the “every polynomial has a root over $\bar{K}$” property is a useful one for algebraic geometry / elliptic curves in particular

- TODO: $\mathbb{A}^n(K)$ = affine $n$-spaces over field $K$

- TODO: quadratic extension $\F_{q^2} = \Fq(i)$ with $i^2 + 1 = 0$

A few notes

The general Weierstrass equation:

\begin{align} \label{eq:general-weierstrass} E : y^2 + a_1 xy + a_3 y = x^3 + a_2 x^2 + a_4 x + a_6 \end{align}

The short Weierstrass equation: \begin{align} \label{eq:short-weierstrass} E : y^2 = x^3 + a x + b \end{align}

How? Assume the field characteristic is not 2 or 3.

Why? I think it’s to allow for the few substitutions below to simplify into short Weierstrass…)

Then, with a few substitutions, we arrive at Equation $\ref{eq:short-weierstrass}$.

If $(a_1, \ldots, a_6)$ come from $K$, then $E$ is said to be defined over $K$, which is denoted as $E / K$.

An elliptic curve group (over a field $K$) is defined as: \begin{align} E(K) = \{(x,y)\in \mathbb{A}^2(K) : y^2 = x^3 + ax + b\} \cup \{\ecid\} \end{align}

Here, $\ecid$ denotes the identity element of $E(K)$, also called the point at infinity. Note that $\ecid$ is a “special case” point that is defined artificially; it does not have any $(x,y)$ coordinates (as we’ll see later).

Note that we typically just have $(x,y)\in K^2$?

$E = E(\bar{K})$ is typically used to refer to the same group defined over the full algebraic closure of $K$. (e.g., when $K = \mathbb{Q}$, $\bar{K}$ is $\mathbb{R}$)

We’ll initially denote the elliptic curve group operation by $\oplus$ (and its inverse by $\ominus$), but at a later point we will replace it with $+$ (and $-$, respectively).

Note that the identity element of $E(K)$ denoted by $\ecid$ is a “special case” point; it is defined artificially.

For any $P\in E(K)$, we denote $\underbrace{P \oplus P \oplus \cdots \oplus P}_{n\ \text{times}} \bydef [n]P$.

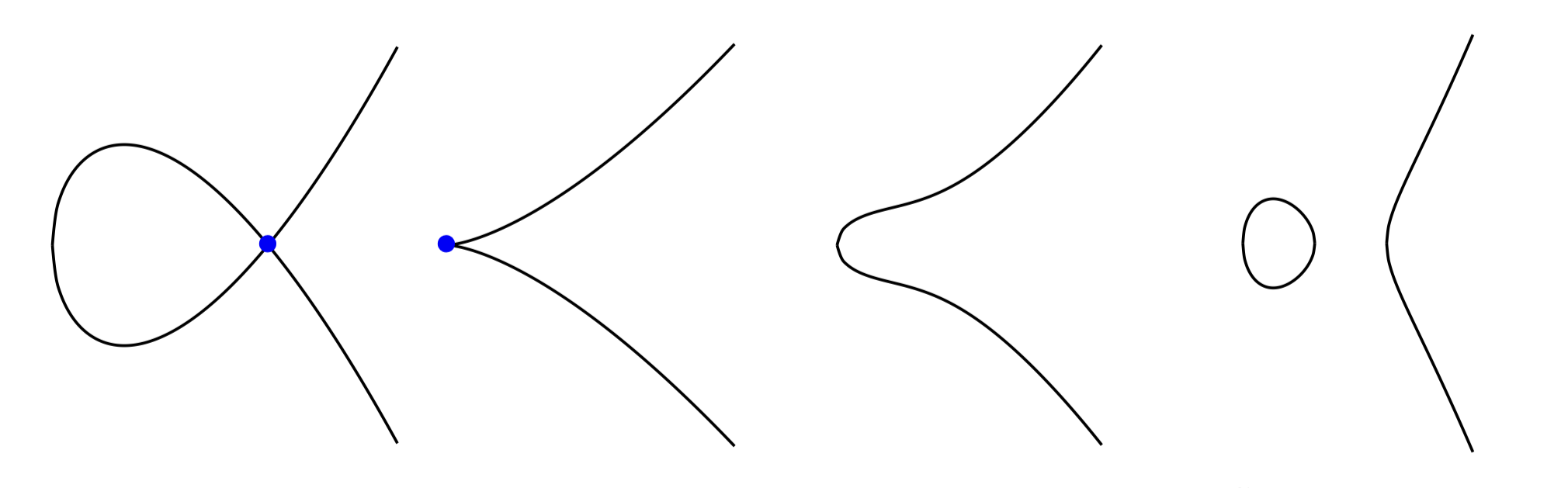

A note on (non)singular elliptic curves, whose future relevance I am unsure of. Q: Why are singular curves bad?

TODOs

- explain group addition law; plus, link to picture

- Why is the 3rd intersection point flipped over (“reflected”) in the additional law? Would DL be easy w/o that?

- Affine vs. projective coordinates

- group axioms

- closure, by virtue of R being the third root of the cubic polynomial (whose first two roots were the points P and Q)

- associativity

- weirstrass model is not ideal for fast impl. of the group addition law

- projective coordinates avoid inversions (may be worth only mentioning it? cause lots of details to cover)

- jacobi quartic form (just mention it; too advanced for now)

- the order of $E(\Fq)$

- Hasse bound

- the CM algorithm

Resources

Acknowledgements

Most screenshots in this post (and most of my understanding of elliptic curves) come from Craig Costello’s “Pairings for beginners.”1.

Thanks to Wicher Malten for reminding me what an algebraic closure is.