tl;dr: Confidential fungible assets (CFAs) are in town! But first, a moment of silence for veiled coins.

Notation

- For time complexities, we use:

- $\Fadd{n}$ for $n$ field additions in $\F$

-

$\Fmul{n}$ for $n$ field multiplications in $\F$

- $\Gadd{\Gr}{n}$ for $n$ additions in $\Gr$

- $\Gmul{\Gr}{n}$ for $n$ individual scalar multiplications in $\Gr$

- $\fmsm{\Gr}{n}$ for a size-$n$ MSM in $\Gr$ where the group element bases are known ahead of time (i.e., fixed-base)

- when the scalars are always from a set $S$, then we use $\fmsmSmall{\Gr}{n}{S}$

- $\vmsm{\Gr}{n}$ for a size-$n$ MSM in $\Gr$ where the group element bases are not known ahead of time (i.e., variable-base)

- when the scalars are always from a set $S$, then we use $\vmsmSmall{\Gr}{n}{S}$

- We assume a prime-order group $\term{\Gr}$ of prime order $\term{p}$

- We use additive group notation: $a \cdot G$ denotes scalar multiplication in $\Gr$, where $a\in \Zp$ and $G\in\Gr$

Confidential asset notation

If we decide to use $b$ for the base, use $w$ for the chunk size!

- $\term{b}$

- chunk size in bits

- $\term{B}=2^b$

- chunk size as an integer

- $\term{\ell}$

- # of available balance chunks

- In Aptos, balances are 128 bits $\Rightarrow \ell\cdot b = 128$

- $\term{n}$

- # of pending balance chunks and # of transferred amount chunks

- In Aptos, transferred amounts are 64 bits $\Rightarrow n \cdot b = 64$

- $\term{t}$

- each account can receive up to $2^t-1$ incoming transfers, after which it needs to be rolled over

- i.e., the owner must send a TXN that rolls over their pending into their available balance

- $\Rightarrow$ pending balance chunks are always $< \emph{2^b(2^t - 1)}$

- $\Rightarrow$ available balance chunks are always $< 2^b + \emph{2^b(2^t - 1)} = 2^b(1 + 2^t - 1) = 2^b 2^t = 2^{b+t}$

- assuming we only roll over into normalized available balances (i.e., with chunks $< 2^b$)

Not sure why our initial implementation used $2^t - 2$ instead of $2^t-1$. May want to write a unit test and make sure my math works.

Preliminaries

We assume familiarity with:

- Public-key encryption

- In particular, Twisted ElGamal

- ZK range proofs (e.g., Bulletproofs1, BFGW, DeKART)

- $\Sigma$-protocols

Naive discrete log algorithm

Naively, computing the discrete logarithm (DL) $a$ on $a \cdot G$ when $a\in[m)$ can be done in constant-time via a single lookup in an $m$-sized precomputed table:

\begin{align} (\jG{j})_{j\in [m)} \end{align}

Baby-step giant step (BSGS) discrete log algorithm

The BSGS algorithm can compute a DL on $a\in[m)$ with much less memory but with more computation. Specifically:

- it reduces the table size from $m$ to $\sqm$

- it increases the time from $O(1)$ to $\GaddG{(\sqm-1)}$.

Let $\term{s}\bydef\sqm$.

The key idea is that we can represent the value $a$ as a 2-digit number $(i,j)$ in base-$\emph{s}$:

\begin{align}

a = i\cdot s + j,\ \text{where}\ i,j\in[s)

\end{align}

As a result finding the discrete log $a$ of $H\bydef a\cdot G$, can be reduced to finding its two digits $i,j\in[s)$ such that:

\begin{align}

H &= (i \cdot s + j)\cdot G\Leftrightarrow\\

H &= i \cdot (s \cdot G) + j \cdot G\Leftrightarrow\\

\label{eq:bsgs-check}

H + i \cdot (\msG) &= \jG{j}

\end{align}

Now, imagine we have all $(\jG{j})_{j\in[s)}$ and $\msG$ precomputed. Then, finding $a$ can be reduced to computing all the left hand sides (LHS) of Eq. $\ref{eq:bsgs-check}$ for all possible $i\in[s)$ and checking if there exists $j\in[s)$ such that the LHS equals the right hand side (RHS). If it does, then $a = i\cdot s+ j$!

More concretely, we compute:

\begin{align}

V_0 &\gets H = H + 0 \cdot (\msG)\\

V_1 &\gets V_0 \msG = H + 1 \cdot (\msG)\\

V_2 &\gets V_1 \msG = H + 2 \cdot (\msG)\\

&\hspace{.7em}\vdots\\

V_i &\gets V_{i-1} \msG = H + i \cdot (\msG)\\

&\hspace{.7em}\vdots\\

V_{s-1} &\gets V_{s-2} \msG = H + (s-1) \cdot (\msG)\\

\end{align}

Then, for each computed $V_i$, we check (in constant-time) whether there exists a $j\in[s)$ such that $V_i = \jG{j}$.

In other words, we check if Eq. \ref{eq:bsgs-check} holds for some $i,j\in[s)$.

If it does, then we solved for the correct DL $a = i\cdot s + j$!

Note that this algorithm will take at most $s-1$ group additions in $\Gr$, so it is very efficient!

The maximum value $a$ can take in this base-$s$ representation is $(s-1) \cdot s + (s-1) = (s-1)(s+1) = s^2 - 1$. Since $\sqm \ge \sqrt{m}$, by squaring it, it follows that $\sqm^2 \ge \sqrt{m}^2\Leftrightarrow s^2 \ge m$. This means $a=m-1$ can be represented in base-$s$, so the algorithm will be able to solve DL for all $a\in[m)$. (Not only: it may also be able to solve it for slightly higher values, e.g., $s=4$ for both $m = 15,16$).

We give formal algorithms for BSGS below.

$\mathsf{BSGS.Precompute}(m\in \N, G\in\Gr) \rightarrow \table$

Recall that $\term{s}\bydef\sqm$.

Compute the table in $\GaddG{(s-1)}$ time and return it: \begin{align} \table \gets (s, (\jG{j})_{j\in[s)}, \msG) \in \N \times \Gr^s \times \Gr \end{align}

$\mathsf{BSGS.Solve}(\table, H\in\Gr) \rightarrow a \in [m)\times \{\bot\}$

Parse the table: \begin{align} (s, (j,\jG{j})_{j\in[s)}, \msG) \parse \table \end{align}

Let $V_0 = H$.

For each $i\in[0, s)$:

- if $\exists j\in[s)$ such that $V_i \equals \jG{j}$, then return $i\cdot s + j$

- $V_{i+1} \gets V_i + (\msG)$

If we reached this point, this means no $i,j\in[s)$ were found. This, in turn, means $a \ge s^2 \ge m$.

Therefore, return $\bot$.

BSGS-$k$ discrete log algorithm

BSGS-$k$ is a variant of BSGS that dramatically speeds up the solve algorithm by batching $k$ giant steps together. When used on Ristretto255 curves, BSGS’s main bottleneck is the expensive point compression required to index into the precomputed table after every giant step. BSGS-$k$ avoids this by first computing $k$ giant steps via $k-1$ group additions and then compressing all $k$ points at once. Unfortunately, batch compression is not supported in Ristretto255. (Feel free to open that can of worms on your own.) But, fortunately, doubled point compression is supported via a $\doubleAndCompressBatch{\cdot}$ algorithm. As a result, we observe that the BSGS algorithm can be adjusted to work over these doubled points!

We give formal algorithms for BSGS-$k$ below, building on the BSGS algorithms above.

$\mathsf{Compress}(H\in \Gr) \rightarrow \{0,1\}^{256}$

Returns a 32-byte (256-bit) compressed canonical representation of the group element $H$.

$\mathsf{DoubleAndCompressBatch}\left((H_i)_{i\in[k]}\in \Gr\right) \rightarrow \left(\{0,1\}^{256}\right)^k$

Doubles all $H_i$’s and compress the results in batch, more efficiently than repeatedly calling $\compress{2\cdot H_i}$ for all $i\in [k]$.

$\mathsf{BSGS\text{-}k.Precompute}(m\in \N, G\in\Gr) \rightarrow \table$

Recall that $\term{s}\bydef\sqm$.

Compute the doubled table in $\GaddG{(s-1)}$ time and return it: \begin{align} \table \gets (s, (\ctwojG{j})_{j\in[s)}, \twomsG) \in \N \times \Gr^s \times \Gr \end{align}

$\mathsf{BSGS\text{-}k.Solve}(\table, H\in\Gr) \rightarrow a \in [m)\times \{\bot\}$

Parse the table: \begin{align} (s, (\ctwojG{j})_{j\in[s)}, \twomsG) \parse \table \end{align}

Let $V_0 = H$.

For each $i\in\{0,k,2k,\ldots\}$ subject to $i < s$:

- Compute $V_{i+1}, \ldots, V_{i+k-1}$ via $k-1$ additions of $\msG$, such that $V_{i+\ell} \bydef H + (i+\ell)\cdot (\msG)$

- Compute $\doubleAndCompressBatch{V_i, V_{i+1}, \ldots, V_{i+k-1}}$ to get compressed points $(c_i, \ldots, c_{i+k-1})$, where $c_{i+\ell} \bydef \compress{2\cdot V_{i+\ell}}$

- For each $\ell \in [0, k)$:

- if $\exists j\in[s)$ such that $c_{i+\ell} \equals \ctwojG{j}$, then return $\ell\cdot s + j$

- $V_{i+k} \gets V_{i+k-1} + (\msG)$

If we reached this point, return $\bot$.

Truncated BSGS-$k$ (TBSGS-$k$) discrete log algorithm

TBSGS-$k$ is a variant of BSGS that dramatically reduces the table size from $\sqm \cdot 32$ bytes to $\sqm \cdot 8$ bytes (a 75% reduction) while maintaining nearly-identical performance for large secrets.

The key idea is to store only truncated 8-byte hashes of the precomputed points rather than full 32-byte compressed points. Specifically, instead of storing $(j, \jG{j})_{j\in[s)}$, we store: \begin{align} \left(\tctwomjG{j}\right)_{j\in[s)} \end{align} where $\term{\mathsf{Trunc}}$ returns the first 8 bytes and $\term{\mathsf{Compress}}$ is the standard Ristretto255 point compression.

We give formal algorithms for TBSGS-$k$ below, building on the BSGS-$k$ algorithms above.

$\mathsf{TBSGS\text{-}k.Precompute}(m\in \N, G\in\Gr) \rightarrow \table$

Recall that $\term{s}\bydef\sqm$.

Compute the truncated doubled table in $\GaddG{(s-1)}$ time and return it: \begin{align} \table \gets \left(s, (\tctwomjG{j})_{j\in[s)}, \twomsG\right) \in \N \times \{0,1\}^{64 \cdot s} \times \Gr \end{align}

$\mathsf{TBSGS\text{-}k.Solve}(\table, H\in\Gr) \rightarrow a \in [m)\times \{\bot\}$

Parse the table: \begin{align} (s, (\tctwomjG{j})_{j\in[s)}, \twomsG) \parse \table \end{align}

Let $V_0 = H$.

For each $i\in\{0,k,2k,\ldots\}$ subject to $i < s$:

- Compute $V_{i+1}, \ldots, V_{i+k-1}$ via $k-1$ additions of $\msG$, such that $V_{i+\ell} \bydef H + (i+\ell)\cdot (\msG)$

- Compute $\doubleAndCompressBatch{V_i, V_{i+1}, \ldots, V_{i+k-1}}$ to get compressed points $(c_i, \ldots, c_{i+k-1})$, where $c_{i+\ell} \bydef \compress{2\cdot V_{i+\ell}}$

- For each $\ell \in [0, k)$:

- Let $t_{i+\ell} \gets \trunc{c_{i+\ell}}$

- if $\exists j\in[s)$ such that $t_{i+\ell} \equals \tctwomjG{j}$, then:

- if $V_{i+\ell} \equals \twojG{j}$ (verify the match), then return $\ell\cdot s + j$

- $V_{i+k} \gets V_{i+k-1} + (\msG)$

If we reached this point, return $\bot$.

Related work

There is a long line of work on confidential asset-like protocols, both in Bitcoin’s UTXO model, and in Ethereum’s account model. Our work builds-and-improves upon these works:

- 2015, Confidential assets2

- 2018, Zether3

- 2020, PGC4

- 2025, Taurus Releases Open-Source Private Security Token for Banks, Powered by Aztec, see repo here

- 2025, Solana’s confidential transfers

Upgradeability

There will be many reasons to upgrade our confidential asset protocol (CFA):

- Performance improvements

- Bugs in $\Sigma$-protocols or ZK range proof

- Post-quantum security

Depending on which aspect of the protocol must change, upgrades can range from trivial to very tricky.

Increasing the # of max pending transfers

The parameter $\emph{t}$ defined above can be increased as long as we can compute discrete logs for values $\le 2^b(2^t - 1)$.

The justification for its $t = 16$ value is discussed later on.

Upgrading ZKPs

This can be done trivially: just add a new enum variant while maintaining the old one for a while.

If there is a soundness bug, the old variant must be disallowed.

This will break old dapps, unfortunately, but that is inherent in order to protect against theft.

Define the CFA algorithms so as to reason about upgradeability more easily.

Upgrading encryption scheme

We may want to upgrade our encryption scheme for efficiency reasons or for security (e.g., post-quantum).

Option 1: Force users to upgrade their balance ciphertexts

One way5 to support such an upgrade is to force the owning user to re-encrypt their obsolete balance ciphertexts under the new encryption scheme. Then, we’d only allow transfers between users who are upgraded to the new scheme. (Option two would be to implement support for sending confidential assets from an obsolete balance ciphertext into an upgraded balance ciphertext.)

Such upgrades may happen repeatedly, so we must ensure complexity does not get out of hand: e.g., if over the years we’ve upgraded our encryption scheme $n-1$ times, then there may be a total of $n$ ciphertext types flying around ($n\ge 1$).

Naively, we’d want to support converting from any obsoleted encryption scheme to any new scheme, but that would require too many re-encryption implementations: $(n-1) + (n-2) + \ldots + 2 + 1 = O(n^2)$.

A solution would be to only implement re-encryption from the $i$th scheme to $(i+1)$th scheme, for any $i\in[n-1]$. This could be slow, since it requires $n-1$ re-encryptions. If so, we can do it in $O(\log{n})$ re-encryptions in a skip list-like fashion. (By allowing upgrades to skip intermediate schemes, we would reduce the number of required re-encryptions.)

Another challenge: post-upgrade, existing dapps, now with an out-of-date SDK, will not know how to handle the new encryption scheme. So, such upgrades are backwards incompatible.

For example, old dapps will be “surprised” to see that the user’s balance is no longer encrypted under the old scheme (i.e., the SDK sees that the balance enum is a new unrecognized variant). If so, the SDK should display a user-friendly error like “This dapp must be upgraded to support new confidential asset features.”

It’s unclear whether there’s something better we could do to maintain backwards compatibility. I think the main problematic scenario is:

- Alice used a new dapp that converted her entire balance to the new scheme

- Alice uses an old dapp that panics when it cannot handle the new scheme

We may want to strongly recommend that dapps/wallets only allow the user to manually upgrade their ciphertexts? This way, at least users understand that upgrading may make their assets inaccessible on older dapps.

Option 2: Universal transfers

Again, the assumption is that, over the years, we’ve upgraded our encryption scheme $n-1$ times $\Rightarrow$ there may be a total of $n$ ciphertext types flying around ($n\ge 1$).

To deal with this, we could simply build functionality that allows to transfer CFAs between any scheme $i,j\in[n]$.

During a send, the SDK should prefer encrypting the amounts for the recipient under the highest supported scheme $j$ their account supports. (Or, encrypt for the max $j$ supported by the contract; it’s just that the user, depending on what dapp/wallet they are using, may not be able to access that balance.)

We could enforce “progress” by only allowing to send from a scheme $i$ to a scheme $j$ when $j > i$, but only when we are certain dapps have been upgraded to the latest SDK so they can handle the new ciphertexts. This way, we would ensure that older ciphertexts don’t proliferate.

FAQ

How does auditing currently work?

Aptos governance can decide, for each token type, who is the auditor for TXNs for that token:

/// Sets the auditor's public key for the specified token.

///

/// NOTE: Ensures that new_auditor_ek is a valid Ristretto255 point

public fun set_auditor(

aptos_framework: &signer, token: Object<Metadata>, new_auditor_ek: vector<u8>

) acquires FAConfig, FAController

This updates the following token-type-specific resource:

/// Represents the configuration of a token.

struct FAConfig has key {

/// Indicates whether the token is allowed for confidential transfers.

/// If allow list is disabled, all tokens are allowed.

/// Can be toggled by the governance module. The withdrawals are always allowed.

allowed: bool,

/// The auditor's public key for the token. If the auditor is not set, this field is `None`.

/// Otherwise, each confidential transfer must include the auditor as an additional party,

/// alongside the recipient, who has access to the decrypted transferred amount.

auditor_ek: Option<twisted_elgamal::CompressedPubkey>

}

There is no global auditor support implemented; only token-specific. (An older version of the code had global auditing only.) However, we do allow anyone to encrypt their TXN’s amounts under any auditor EK they please, not just the token-specific auditors that may (or may not) be “installed” on-chain. In other words, only the first auditor EK is required to be the set to the token-specific auditor.

We do not require a ZKPoK when setting a token-specific EK, to simplify deployment and implementation. It can be easily added in the future.

Why 16-bit chunk sizes?

We chose $b=16$-bit chunks for two reasons.

First, it allows us to use the naive DL algorithm to instantly decrypt TXN amounts. This should make confidential dapps very responsive and fast.

Second, it ensures that, after $2^{\emph{t}} - 1$ incoming transfers, the pending balance chunks never exceed $2^b(2^t-1)$. For example, for $t = 16$ (i.e., for $\le$ 65,535 incoming transfers), the pending balance chunks will remain $\le 2^{16}(2^{16} - 1) = 2^{32} - 2^{16} < 2^{32}$. This, in turn, ensures fast decryption times for pending (and available) balances.

Why do we think there could be so many incoming transfers? They may arise in some use cases, such as payment processors, where it would be important to seamlessly receive many transfers. In fact, $2^{16}$ may not even be enough there. (Fortunately, the $t$ parameter is easy to increase as we deploy faster DL algorithms.)

What are the main tensions in the current ElGamal-based design

The main tension is between:

- The ElGamal ciphertext (and associated proof) sizes: i.e., the # of chunks $n$ and $\ell$

- The decryption time for a TXN’s amount: i.e., the chunk size $b$

- We must be able to compute $n$ DLs on $b$ bit values in less than 10ms in the browser

- This seems to restrict us to $b \le 16$ (TODO: include TypeScript benchmarks here)

- We must have $\ell \cdot b=128$ and $n \cdot b = 64$

- From above, we get $\ell = 8$ and $n=4$

- This also indirectly influences the balance decryption times: balance chunks DLs are $(b+t)$-bit

- DL times are fast for 32 bits $\Rightarrow t = 16$

- Fortunately, as we improve our DL algorithms, we can simply increase $t$, in a backwards compatible fashion.

- We must be able to compute $n$ DLs on $b$ bit values in less than 10ms in the browser

We can make decryption arbitrarily fast by encrypting smaller chunks, but we would increase confidential transaction sizes and also the cost to verify them due to more $\Sigma$-protocol verification work. This would drive up gas costs.

Important open question: Minimizing the impact of higher $n$ and $\ell$ on our $\Sigma$-protocols using some careful design would be very interesting!

Follow up question: How fast is univariate DeKART?

Note that if we use DeKART, as we make the chunk size $b$ smaller, even though the # of chunks $\ell$ (and $n$) increase, the range proof size and the verification time will actually decrease!

And we can speed up the verification time further: instead of proving that the chunks are in $[2^b)$, we can prove that they are in $[(2^k)^{b/k})$ and get a $k$ times smaller proof with faster verification (TBD).

So we have to find a sweet spot. Currently, we believe this to be either $b=8$-bit or $b=16$-bit chunks. (TBD.)

A secondary tension is between:

- The # of incoming transfers $2^t - 1$ we allow without requiring a rollover from the pending balance into the available balance

- The max discrete log instance we are willing to ever solve for via specialized algorithms like [BL12]6

- This instance would arise when decrypting the pending or the available balance

One of the difficulties is that [BL12]6 is a probabilistic algorithm. This seems harmless, in theory, but we’ve actually encountered failures that are hard to debug when confidential apps are deployed. Furthermore, our current [BL12]6 implementation is in WASM (compiled from Rust) which increases the size of confidential dapps, complicates our code and makes debugging harder.

So, for ease of debugging, ease of implementing and for a consistent UX, we’d prefer deterministic algorithms that are guaranteed to terminate in a known amount of steps, like BSGS. This way, we can guarantee none of our users will ever run into issues.

Unfortunately, deterministic algorithms are slower: BSGS on values in $[m)$ takes $O(\sqrt{m})$ time and space while [BL12]6 only takes $O(m^{1/3})$ time and space. This means that the highest $m$ we can hope to use with BSGS is in $[2^{32}, 2^{36})$, or so. So, our $b+t=32$.

How many types of discrete log instances do you have to solve?

Recall that:

- Transferred amounts are 64-bits and chunked into $b$-bit chunks.

- Balances are 128-bit and also $b$-bit chunked $\Rightarrow$ they have double the # of chunks

- Also, balances “accumulate” transfers in

So, we have to solve two types of DL instances.

- We need to repeatedly decrypt TXN amounts $\Rightarrow$ need very fast DL algorithm for $b$-bit values

- We need to one time decrypt the pending and available balance $\Rightarrow$ we need a reasonably-fast DL algorithm for $\approx (b + t)$-bit values, if we want to support up to $\emph{2^t}$ incoming transfers

To what extent can users provide hints in their TXNs and/or accounts to speed up decryption?

First, for TXN amounts, the chunk sizes are picked so that decryption is very fast. We will likely implement $O(1)$-time decryption with a table of size $2^{16} \cdot 32 = 2^{21}$ bytes $= 2$ MiB. As a result, there is no hint that the sender can include to make this decryption faster.

Open question: How much can we hope to reduce this table size?

Ideally, we are looking to have $\mathcal{H} : \{ j\cdot G : j\in[m)\} \rightarrow [m)$ with $\mathcal{H}(j\cdot G) = j,\forall j\in[m)$.

Such an ideal hash function may need at least $2^m \cdot \log_2{m} = 2^{m+\log_2\log_2{m}}$ bits.

Follow up question: Would this help reduce storage for BSGS?

I think so, yes!

Second, for pending balances, it’s tricky because they change constantly as the user is getting paid. Viewed differently, the hints are the decrypted amounts in all TXNs received since the last rollover which, as explained above, are very fast to fetch.

A key question:

Should we decrypt pending balances by doing $n$ DLs of size $<2^b(2^t - 1)$ each?

Or should we give ourselves a way to fetch the last $2^t$ TXNs, instantly decrypt them and add them up?

Decision:

To minimize impact on our own full nodes and/or indexers, and since we’ll need a DL algorithm for available balances anyway (see below), we should decrypt pending balances manually.

We can of course change this in the future.

Third, for available balances, this is where the sender can indeed store a hint for themselves. The sender can do so:

- After sending a TXN out, which decreases their available balance

- After normalizing their available balance

If:

- Dealing with incorrect hints is not too expensive/cumbersome to implement

- Storing the hint is not too expensive, gas-wise.

- Decrypting the hint is significantly faster than doing $\ell$ DLs of size $< 2^{b+t}$ each

…then the complexity may be warranted.

On the other hand, if using $b+t = 32$ bits, then I estimate that a 32-bit discrete log via BSGS will take around 1 second in the browser (i.e., 13 ms $\times$ 10x slowdown${}\times \ell$ chunks $= 13$ ms${} \times 10 \times 8$ chunks $= 1.04$ seconds).

Decision: Either way, we need a DL algorithm for $(b+t)$-bit values in case the hint is wrong/corrupted by bad SDKs. So, for now, we adopt the simpler approach, but we should leave open the possibility of adding hints in the future.

We can allow for “extensions” fields in a user’s confidential asset balance.

Maybe make it an enum.

How smart can the SDK be to avoid decryption work?

Should the SDK just poll for a change in the encrypted balances on-chain and decrypt them? (Simple, but slow if user is receiving lots of transfers.)

Or should the SDK be more “smart” and be aware of the last decrypted balance and the transactions received since, including rollovers and normalizations? (Complex, but much more efficient.)

One challenge with the “smart” approach is that the SDK may need to fetch up to $2^t-1$ payment TXNs plus extra rollover and normalization TXNs.

This is an open question for our SDK people.

Why not go for a general-purpose zkSNARK-based design?

Question: Why did Aptos go for a special-purpose design based on the Bulletproofs ZK range proof and $\Sigma$-protocols, rather than a design based on a general-purpose zkSNARK (e.g., Groth16, PLONK, or even Bulletproofs itself)?

Short answer: Our special-purpose design best addresses the tension between efficiency and security.

Long answer: General-purpose zkSNARKs are not a panacea:

- They remain slow when computing proofs

- This makes it slow to transact confidentially on your browser or phone.

- They may require complicated multi-party computation (MPC) setup ceremonies to bootstrap securely

- This makes it difficult and risky to upgrade confidential assets if there are bugs discovered, or new features are desired

- Implementing any functionality, including confidential assets, as a general-purpose “ZK circuit” is a dangerous minefield (e.g., circom)

- It is very difficult to do both correctly & efficiently7

- To make matters worse, getting it wrong means user funds would be stolen.

Still, general-purpose zkSNARK approaches, if done right, do have advantages:

- Smaller TXN sizes

- Cheaper verification costs.

So why opt for a special-purpose design like ours?

Because we can nonetheless achieve competitively-small TXN sizes and cheap verification, while also ensuring:

- Computing proofs is fast

- This makes it easy to transact on the browser, phone or even on a hardware wallet

- There is no MPC setup ceremony required

- This makes upgrades easily possible

- The implementation is much easier to get right

- We can sleep well at night knowing our users’ funds are safe

Appendix: Links

Slides:

Documentation & articles:

- aptos.dev docs

- Build with Confidential Transactions on Aptos

- Aptos Improvement Proposal (AIP) 143: Confidential APT

Repositories:

- Ristretto255 discrete logarithm algorithms

- WASM bindings for DL algorithms and Bulletproofs

- Move contract

- TypeScript SDK

- Confidential payments demo webapp

Apps:

v1.1 pull requests (PRs)

- Move contract in aptos-core

- DL algorithms in ristretto255-dlog

- WASM bindings for DL algorithms and Bulletproofs in confidential-asset-wasm-bindings

- SDK in aptos-ts-sdk

- aptos.dev docs in aptos-docs

- Confidential payments demo webapp in confidential-payments-example

Appendix: Benchmarks

All benchmarks are run single-threaded on an Apple Macbook Pro M4 Max.

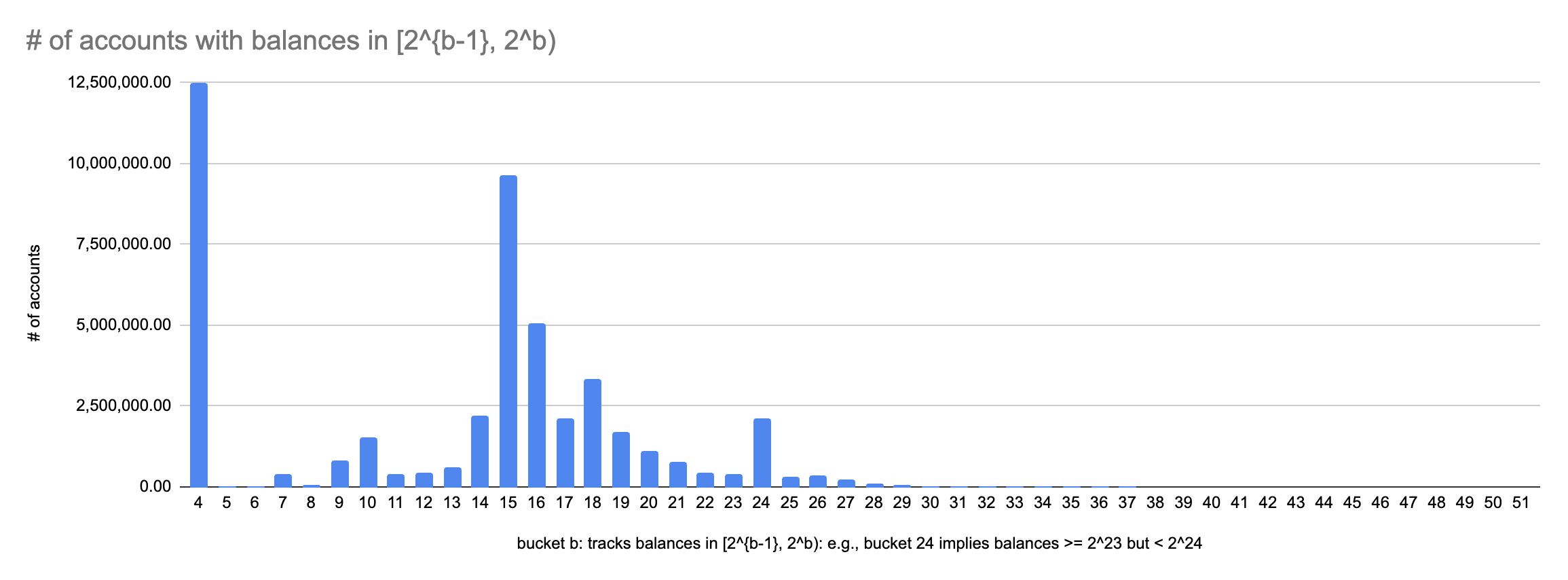

Bit-widths of Aptos balances (in octas) on mainnet

tl;dr: One third have at most 1, 2, 3 or 4 bits. 18% have 15 bits. 15% have 14 or 16 bits. Graph below 👇

Ristretto255: curve-dalek25519-ng microbenchmarks

ristretto255 point compression

time: [3.7242 µs 3.7265 µs 3.7290 µs]

ristretto255 point addition

time: [126.28 ns 127.90 ns 130.90 ns]

Unfortunately, Ristretto255 is cursed: it needs canonical square roots computed during point compression, which are not batchable. (This is inherent for any Decaf-like group, it seems.) This means that the DL algorithms are dominated by point-compression necessary to index into the precomputed tables.

Discrete log precomputed table sizes

| Algorithm | Size |

|---|---|

| TBSGS-k 32-bit | 512 KiB |

| BSGS 32-bit | 2.00 MiB |

| BSGS-k 32-bit | 2.00 MiB |

| BL12 32-bit | 258 KiB |

TBSGS-k is the default algorithm, offering the best balance of WASM size and performance.

MPHF-based table sizes (not used)

| Algorithm | HashMap | MPHF-based | Reduction |

|---|---|---|---|

| BSGS 32-bit | 2.50 MiB | 534 KiB | 79% |

| BSGS-k 32-bit | 2.50 MiB | 534 KiB | 79% |

| Naive Lookup 16-bit | 2.50 MiB | 534 KiB | 79% |

This was an experiment gone wrong, because MPHFs cannot detect “key not in set” - it always returns some index. For BSGS where most lookups are misses, this is unacceptable without storing keys alongside (defeating the space savings).

Plus, truncating the table is even more effective.

But this may be due to the initially-naive MPHF implementation: may have stored values in u64’s?

WASM size

Currently, WASM size is 774 KiB. Most of this is just the 512 KiB precomputed table for TBSGS-$k$.

git clone https://github.com/aptos-labs/confidential-asset-wasm-bindings

cd confidential-asset-wasm-bindings/

./scripts/wasm-sizes.sh

This unified WASM combines both discrete log and range proof functionality into a single module, sharing the curve25519-dalek elliptic curve library.

Rust DLP: [BL12]6

[BL12] 32-bit secrets time: [4.6197 ms 4.8080 ms 5.0194 ms]

On my old M1 Max, for 48 bits, BL12 times were: [763.90 ms 1.1598 s 1.6174 s].

Rust DLP: (Truncated-)BSGS with batch size $k$

Summary: TBSGS-k (Truncated BSGS-k) stores only 8-byte truncated keys instead of full 32-byte points, reducing table size from 2.0 MiB to 512 KiB (75% reduction). For 32-bit secrets, TBSGS-k performs identically to BSGS-k (~11 ms). For smaller secrets, TBSGS-k is ~3x slower due to verification overhead (one scalar multiplication per match), but this is negligible in absolute terms (35 µs vs 12 µs). TBSGS-k should be preferred for its dramatically smaller table size with minimal performance impact.

For discrete logs on 32-bit values with tables for 32-bits:

[BSGS-k1], 32-bit secrets

time: [61.928 ms 67.501 ms 77.980 ms]

[TBSGS-k1], 32-bit secrets

time: [64.498 ms 69.626 ms 74.543 ms]

[BSGS-k2], 32-bit secrets

time: [40.716 ms 42.236 ms 44.658 ms]

[TBSGS-k2], 32-bit secrets

time: [41.303 ms 43.666 ms 46.133 ms]

[BSGS-k4], 32-bit secrets

time: [24.406 ms 25.578 ms 26.663 ms]

[TBSGS-k4], 32-bit secrets

time: [25.164 ms 26.253 ms 27.185 ms]

[BSGS-k8], 32-bit secrets

time: [16.921 ms 17.727 ms 18.506 ms]

[TBSGS-k8], 32-bit secrets

time: [17.375 ms 18.174 ms 18.895 ms]

[BSGS-k16], 32-bit secrets

time: [12.398 ms 13.299 ms 14.351 ms]

[TBSGS-k16], 32-bit secrets

time: [12.851 ms 13.537 ms 14.255 ms]

[BSGS-k32], 32-bit secrets

time: [11.833 ms 12.347 ms 12.783 ms]

[TBSGS-k32], 32-bit secrets

time: [11.379 ms 12.037 ms 12.533 ms]

[BSGS-k64], 32-bit secrets

time: [11.760 ms 12.257 ms 12.909 ms]

[TBSGS-k64], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.717 ms 11.302 ms 11.772 ms]

[BSGS-k128], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.264 ms 10.677 ms 11.013 ms]

[TBSGS-k128], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.363 ms 10.843 ms 11.202 ms]

[BSGS-k256], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.674 ms 11.057 ms 11.478 ms]

[TBSGS-k256], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.512 ms 10.976 ms 11.631 ms]

[BSGS-k512], 32-bit secrets

time: [9.8338 ms 10.664 ms 11.260 ms]

[TBSGS-k512], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.967 ms 11.461 ms 12.073 ms]

[BSGS-k1024], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.329 ms 11.076 ms 11.718 ms]

[TBSGS-k1024], 32-bit secrets

time: [11.144 ms 11.453 ms 11.714 ms]

[BSGS-k2048], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.394 ms 10.811 ms 11.373 ms]

[TBSGS-k2048], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.800 ms 11.248 ms 11.783 ms]

[BSGS-k4096], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.686 ms 11.277 ms 11.681 ms]

[TBSGS-k4096], 32-bit secrets

time: [10.911 ms 11.467 ms 12.043 ms]

[BSGS-k8192], 32-bit secrets

time: [11.520 ms 12.029 ms 12.341 ms]

[TBSGS-k8192], 32-bit secrets

time: [11.663 ms 12.255 ms 12.650 ms]

[BSGS-k16384], 32-bit secrets

time: [12.228 ms 13.168 ms 14.037 ms]

[TBSGS-k16384], 32-bit secrets

time: [13.009 ms 13.615 ms 14.469 ms]

For discrete log on 17-24 bit values but with the same tables for 32 bits, demonstrating that smaller values are solved for faster:

[BSGS-k32], 17-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [12.096 µs 12.118 µs 12.144 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 17-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [35.155 µs 35.252 µs 35.368 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [12.144 µs 12.166 µs 12.189 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [35.003 µs 35.073 µs 35.164 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 19-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [12.211 µs 12.234 µs 12.261 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 19-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [35.060 µs 35.131 µs 35.218 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 20-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [12.286 µs 12.307 µs 12.331 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 20-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [35.063 µs 35.098 µs 35.137 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 21-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [12.424 µs 12.444 µs 12.466 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 21-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [35.119 µs 35.153 µs 35.190 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 22-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [18.917 µs 18.954 µs 18.999 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 22-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [41.477 µs 41.553 µs 41.628 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 23-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [31.782 µs 31.871 µs 31.971 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 23-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [54.167 µs 54.306 µs 54.453 µs]

[BSGS-k32], 24-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [57.521 µs 57.709 µs 57.893 µs]

[TBSGS-k32], 24-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [79.229 µs 79.522 µs 79.798 µs]

For varying K values with 18-bit secrets:

[BSGS-k64], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [22.715 µs 22.763 µs 22.816 µs]

[TBSGS-k64], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [45.064 µs 45.104 µs 45.144 µs]

[BSGS-k128], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [43.323 µs 43.387 µs 43.456 µs]

[TBSGS-k128], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [65.512 µs 65.641 µs 65.812 µs]

[BSGS-k1024], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [338.10 µs 338.59 µs 339.12 µs]

[TBSGS-k1024], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [354.13 µs 354.48 µs 354.88 µs]

[BSGS-k2048], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [673.72 µs 674.26 µs 674.87 µs]

[TBSGS-k2048], 18-bit secrets (32-bit table)

time: [681.17 µs 681.61 µs 682.10 µs]

Decision: Stick with 16 bit chunks and use the naive DL algorithm: store all solutions in tables of $2^{16}$ group elements ($2^{16}\times 32$ bytes $\Rightarrow 2$ MiB) and compute the DL in constant time, when chunks are small! When chunks are big, resort to TBSGS-k or to [BL12]6. We have to be conservative because a user may be using multiple confidential apps at the same time and/or the browser may be busy doing other things.

Rust DLP: BSGS (compression after every step)

[BSGS] 32-bit secrets time: [63.673 ms 69.557 ms 75.040 ms]

WASM DLP: [BL12]6

These were run on an older version of the TS SDK repo via: pnpm jest discrete-log

WASM [BL12] 16-bit: avg=0.24ms, min=0.19ms, max=0.30ms

WASM [BL12] 32-bit: avg=42.59ms, min=34.17ms, max=56.06ms

WASM DLP: TBSGS-$k$ and NaiveTruncatedDoubledLookup

WASM NaiveTruncatedDoubledLookup 16-bit: avg=1.50ms, min=1.33ms, max=2.29ms

WASM TBSGS-k32 32-bit: avg=20.15ms, min=1.84ms, max=39.55ms

TypeScript DLP: BSGS

These were run in the TS SDK repo via: pnpm jest discrete-log

TS BSGS 16-bit: avg=7.47ms, min=5.82ms, max=8.24ms

TS BSGS 32-bit: avg=2252.36ms, min=1539.60ms, max=3359.79ms

Gas benchmarks for confidential_asset v1.1 Move module

The full gas benchmark logs are here, but a nicer summary follows below:

| Operation | Gas | Cost (cents) | # of calls / $1 |

|---|---|---|---|

| register | 1,282 | 0.1282 | 780 |

| deposit | 18 | 0.0018 | 55,555 |

| rollover | 13 | 0.0013 | 76,923 |

| rotate key | 37 | 0.0037 | 27,027 |

| withdraw (no auditor) | 204 | 0.0204 | 4,901 |

| withdraw (eff. auditor, subsequent) | 224 | 0.0224 | 4,464 |

| withdraw (eff. auditor, initial) | 330 | 0.0330 | 3,030 |

| transfer (no auditors) | 305 | 0.0305 | 3,278 |

| transfer (1 extra only) | 315 | 0.0315 | 3,174 |

| transfer (2 extra only) | 324 | 0.0324 | 3,086 |

| transfer (3 extra only) | 334 | 0.0334 | 2,994 |

| transfer (eff. auditor only, subsequent) | 333 | 0.0333 | 3,003 |

| transfer (eff. + 1 extra, subsequent) | 343 | 0.0343 | 2,915 |

| transfer (eff. + 2 extra, subsequent) | 352 | 0.0352 | 2,840 |

| transfer (eff. + 3 extra, subsequent) | 362 | 0.0362 | 2,762 |

| transfer (eff. auditor only, initial) | 438 | 0.0438 | 2,283 |

| transfer (eff. + 1 extra, initial) | 449 | 0.0449 | 2,227 |

| transfer (eff. + 2 extra, initial) | 457 | 0.0457 | 2,188 |

| transfer (eff. + 3 extra, initial) | 468 | 0.0468 | 2,136 |

“Initial” means this is the 1st call with an effective auditor $\Rightarrow$ it stores, for the 1st time, the auditor’s EK component in the user’s available balance $\Rightarrow$ higher gas cost due to storage fee. This is a one-time penalty though: only incurred when the call is 1st made. “Subsequent” refers to subsequent calls that reuse this auditor EK component and thus no longer incur a storage fee $\Rightarrow$ this is the “average case” that we care about when reasoning about gas costs.

v1.0 → v1.1 speedup

| Operation | v1.0 gas | v1.1 gas | Speedup |

|---|---|---|---|

| register | 1,276 | 1,282 | ~same (storage-dominated) |

| deposit | 19 | 18 | ~same |

| rollover | 13 | 13 | same |

| rotate key | 215 | 37 | 5.81x |

| withdraw | 215 | 204 | 1.05x |

| transfer | 339 | 305 | 1.11x |

For the old code, see v1.0 gas benchmark logs here.

Appendix: Implementation challenges

Move serialization of handle-based “native” structs like RistrettoPoint

We cannot easily deserialize structs like:

/// A sigma protocol *proof* always consists of:

/// 1. a *commitment* $A \in \mathbb{G}^m$

/// 2. a *response* $\sigma \in \mathbb{F}^k$

struct Proof has drop {

A: vector<RistrettoPoint>,

sigma: vector<Scalar>,

}

…because RistrettoPoint just contains a Move VM handle pointing to an underlying Move VM Rust struct.

We instead have to define a special de-serializable type:

struct SerializableProof has drop {

A: vector<CompressedRistretto>,

sigma: vector<Scalar>,

}

…because CompressedRistretto is serializable: it just wraps a vector<u8>.

Then, we have to write some custom logic in Move that deserializes bytes into a Proof by going through the intermediate SerializableProof struct.

But we cannot even write from_bcs::from_bytes<SerializableProof>(bytes) in Move, because a publicly-exposed from_bytes would allow anyone to create any structs they want, which breaks Move’s “structs as capabilities” security model.

So, in the end, we just have to write a function like this for every struct we need deserialized:

fun deserialize_proof(A: vector<vector<u8>>, sigma: vector<vector<u8>>): Proof

Annoying.

Alternatively, but probably more expensive, since we are writing Aptos framework code, we could make aptos_framework::confidential_asset a friend of aptos_framework::util and call unsafe BCS deserialization code to obtain an intermediate SerializableProof struct:

use aptos_framework::util;

fun deserialize_proof_bcs(bytes: vector<u8>): Proof {

let proof: SerializableProof = util::from_bytes(bytes);

sigma_protocols::proof::from_serializable_proof(proof)

}

…but we still have to, more, or less, manually write code for each struct that converts between its “serializable” counterpart and its actual counterpart.

So, by that point, we may as well just implement deserialize_proof() and deserialize_<struct>() in general for all of our structs.

Annoying.

References

For cited works, see below 👇👇

-

Bulletproofs: Short Proofs for Confidential Transactions and More, by B. Bünz and J. Bootle and D. Boneh and A. Poelstra and P. Wuille and G. Maxwell, in 2018 IEEE Symposium on Security and Privacy (SP), 2018 ↩

-

Confidential transactions, by Gregory Maxwell, 2015, [URL] ↩

-

Zether: Towards Privacy in a Smart Contract World, by Bünz, Benedikt and Agrawal, Shashank and Zamani, Mahdi and Boneh, Dan, in Financial Cryptography and Data Security, 2020 ↩

-

PGC: Pretty Good Decentralized Confidential Payment System with Auditability, by Yu Chen and Xuecheng Ma and Cong Tang and Man Ho Au, in Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2019/319, 2019, [URL] ↩

-

I wonder if this is generally true… ↩

-

Computing small discrete logarithms faster, by Daniel Bernstein and Tanja Lange, 2012, [URL] ↩ ↩2 ↩3 ↩4 ↩5 ↩6 ↩7

-

Writing efficient and secure ZK circuits is extremely difficult. I quote from a recent survey paper8 on implementing general-purpose zkSNARK-based systems: “We find that developers seem to struggle in correctly implementing arithmetic circuits that are free of vulnerabilities, especially due to most tools exposing a low-level programming interface that can easily lead to misuse without extensive domain knowledge in cryptography.” ↩

-

SoK: What don’t we know? Understanding Security Vulnerabilities in SNARKs, by Stefanos Chaliasos and Jens Ernstberger and David Theodore and David Wong and Mohammad Jahanara and Benjamin Livshits, 2024 ↩