tl;dr: “If you thought before that science is certain, well, that’s just an error on your part.” – Richard Feynman

I once ran into a video where Neil deGrasse Tyson, in relation to a debate with folks who didn’t “believe”1 in global warming nor in evolution, said the following:

“The good thing about science is that it’s true whether or not you believe in it” – Neil deGrasse Tyson

You can see the short video below:

The misconception: Science is not intrinsically “true”

The way to conceptualize, and popularize2, science is not as being “true” or “false.”

Science is a process that we engage in to discover truths. And it often leads us astray3$^,$4, which is why the idea of “science being true” is at best misleading and at worst dangerous.

Science is not a belief in any sense of the word. Although many religions might be based on belief, science is an entirely different beast.

Science requires not belief, but experimentation, theory postulation and theory falsification (or refinement).

Those are fancy words, but here’s an example everyone can understand:

Question: How might we find out if there is a universal acceleration that falling objects have? Is it $5\ m/s^2$? Is it $10\ m/s^2$?

Poor answer: We could just blindly accept whatever answer Neil DeGrasse Tyson gives us. After all “science is true whether you believe it or not,” no?

Better answer: No. That is a kind of “scientism” akin to religious belief. Instead, we could engage in the scientific process:

- Experimentation:

- Drop apples of different sizes several times from the same height

- Measure the time they take to fall down

- Compute each apple’s acceleration

- Observe that all apples, no matter their size, have the same acceleration $g\approx 9.8\ m/s^2$

- Theory postulation:

- Propose a theory that says, “When dropped on Earth, all objects accelerate with $9.8\ m/s^2$”.

- Falsification:

- Notice that, for some objects like a light feather, they drop with a smaller acceleration.

- Therefore, your proposed theory above is actually false, since it does not hold for feathers.

- Refine it as: “When dropped in a vacuum on Earth all objects accelerate with $9.8\ m/s^2$”5.

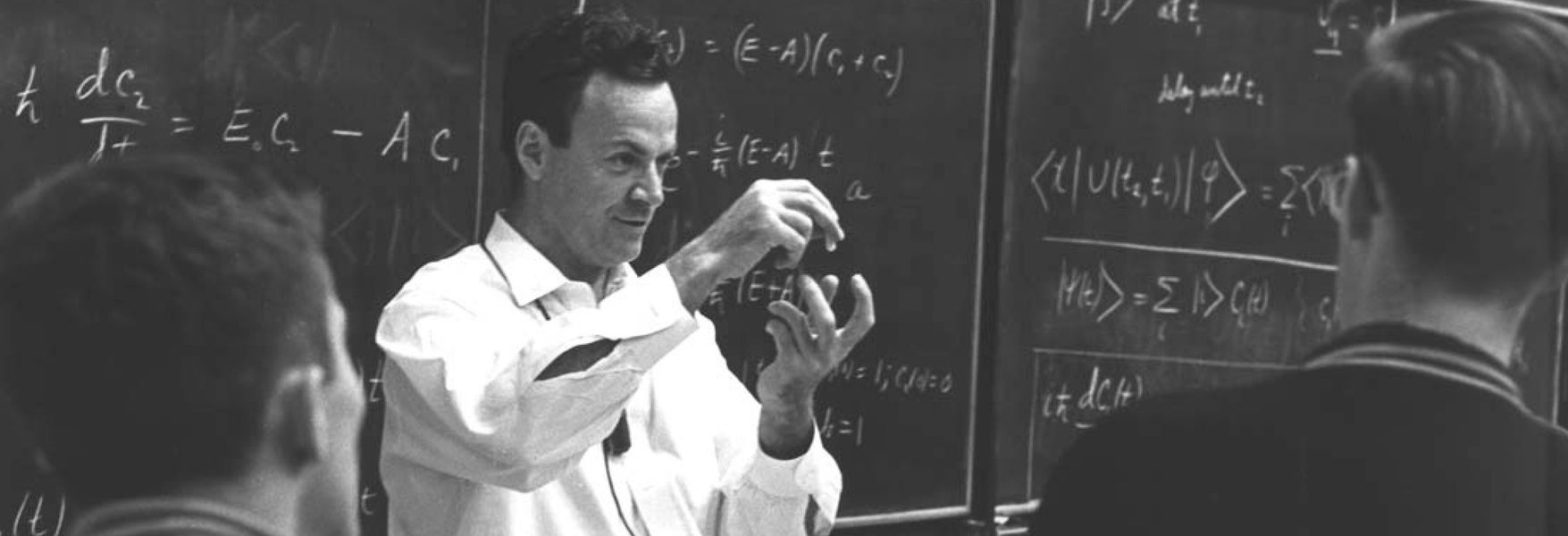

Richard Feynman on the uncertainty of science

Richard Feynman, a physicist you might know6 from his work on quantum electrodynamics (QED)7, explains very beautifully:

What is inherent in science is not “truth” but “uncertainty.”

In one of his famous physics lecture, Feynman beautifully elucidates the leap of faith scientists must make when going from a concrete scientific experiment to a general law that predicts beyond what the experiment tested for.

I include an excerpt below, but I find the video to be much more convincing (and entertaining) to watch:

In the video above, Feynman genuinely asks the audience:

Why are we able to extend our laws to regions that we’re not sure?

How is it possible?

Why are we so confident??

He then explains that extending such general laws is the thing we must do if we are to learn anything new beyond the outcome of the concrete experiment. The price we pay, of course, is we (scientists) stand to be proven wrong in the future. In other words, the nature of scientific laws or theories is they are uncertain, subject to be fully-falsified or partially-refined.

It’s not a mistake to say that [the law] is true in a region where you haven’t looked yet.

If you will not say that it’s true in a region that you haven’t looked yet, [then] you don’t know anything!

[In other words,] If the only laws that you find are those which you just finished observing, then… you can’t make any predictions!

[But] the only utility of the science is to go on and to try and make guesses.

[…]

So what we do is always to stick our neck out!

And that of course means that the science is uncertain!

[…]

We always must make statements about the regions that we haven’t seen, or [else] there’s no use in the whole business.

Feynman reiterates on this point to make it stick:

We do not know all the conditions that we need for an experiment!

[…]

So in order to have any utility at all to the science…

In order not simply to describe an experiment that’s just been done, we have to propose laws beyond their range.

And there’s nothing wrong with that. That’s the success; that’s the point!

And, uhh, that makes the science uncertain.

If you thought before that science is certain, well, that’s just an error on your part.

The solution: Understanding and engaging with science

Please don’t be fooled into thinking “science is true” (whatever that’s supposed to mean). Such claims are nonsensical.

First, they are nonsensical, because science is a process. Processes cannot be “true” or “false”; they are just a way of doing things. Second, because scientific theories are (mostly) falsifiable, which is a fancy way of saying there is room to prove them wrong. (i.e., they might actually be false!)

If one cannot rely on science “to be true”, what should one do instead?

The first option is to take a scientific theory and try to falsify it. For example, Einstein picked Newton’s laws of motion, showed they cannot properly describe motion for objects moving close to the speed of light and generalized them. And that’s how we got the general theory of relativity and, apparently, GPS on our phones.

Note: I look at this as falsifying Netwon’s theories, which were simply not going to work accurately in Einstein’s extreme conditions, while others might look at it as refining them (since Newton’s laws of motion still approximate things very well).

The second option is to devise an experiment, make some observations, generalize them into a theory, and see if your theory holds water by checking if it can predict anything useful. Then, you can go back to the first option and try to falsify your theory.

In other words, engage in science as opposed to “believing in science.”

If you must “believe in science [the scientific process]”, realize you are simply deferring to the authority of other scientists and the soundness of the scientific peer review process.

Yet other scientists are people like you and me.

And we make mistakes, are inherently ignorant or have perverse incentives8.

I recognize that engaging in the scientific process is a very high bar to meet. I also recognize it’s not clear how to reach consensus faster on scientific theories of high importance such as anthropogenic climate change. But I do know that preaching “science is true; believe science” is a steadfast way of moving from scientific (falsifiable) territory into religious (unfalsifiable) territory. This would defeat the original goals of science: to ensure we find out when we are wrong and, as a result, get a bit closer to the truth.

Digression on non-falsifiable (and thus non-scientific) theories

The most widely-accepted philosophy of science comes from Karl Popper, who argued that a theory or statement is scientific only if it can, in principle, be empirically disproven, a.k.a. falsified.

In simpler words words, if a theory does not admit any tests that could prove it false, then that theory is not scientific.

But not all philosophers of science agree with Popper. Some argue that scientific theories must be both falsifiable and empirically-confirmed (to some degree).

Others argue that scientific theories can be unfalsifiable “in practice” as long as they either:

- Are part of broader theoretical frameworks that are testable as a whole.

- Could become falsifiable with future, better technology (e.g., string theory). In this last case, indirect evidence, logical coherence, and the theory’s ability to explain and predict phenomena is what gets the theory to be viewed as scientific.

Nonetheless, the power of scientific (unfalsifiable) theories and of the scientific method does not mean we should dispense with all unfalsifiable theories! That would be anti-human, as I’ll argue below.

A contrived-but-simple example: your friend tells you “There exist pink cars with yellow stripes!” That is an unfalsifiable theory; it would be impossible to disprove. You’d have to somehow show your friend that all cars in the universe don’t match this description, which would take infinite time. Yet, despite being unfalsifiable (and thus unscientific), the theory can be shown to be true by a trivial observation of such a car. And indeed, I know a person with such a car (so I know the theory to be true)!9

So, should you dismiss every unfalsifiable (non-scientific) theory coming out of people’s mouths? No, because we all make such unfalsifiable statements all the time and we get along just fine: e.g., “I had a delicious almond croissant this morning.”

Another example: religious theories (e.g., “there is a God”) fall into the same category of unfalsifiable but potentially-true theories. In fact, people who claim to have had direct experiences of the divine are firmly-convinced of their veracity. Much like your friend above who saw a pink car with yellow stripes that you did not see.

This is not to say that religious theories should be thrown away (i.e., I recognize the limitations of my own consciousness). But it is to say that one should be very careful how they act on such theories. After all, if the religious theory is false, there is no way to find out; it’s unfalsifiable!

Pro tip: In layman terms, don’t burn or kill people because they don’t hold the same unfalsifiable beliefs as you.

I’ll leave you with a last example. My wise mother once threw this at me when I was being a smartass about how bad unfalsifiable theories can be. She said “Okay, how about the theory that love exists in the world. Are you gonna throw away that theory too because it’s unfalsifiable?”. (If you don’t know this theory to be true, then you have other problems and I wish I could give you a warm hug.)

Conclusion

Science is not simply “true”. It is a process that you could engage in. It is not an axiom that you take for granted. It is not an authority that you defer to.

If you don’t have time to engage in science, you can trust-but-verify. However, there is a risk you’ll be deceived by:

- “scientific” “experts”

- “scientific” evidence

- “scientific” truth

- claims that “science” shows that $X$ causes $Y$

- claims that “studies” show

Sentences like these should be critically inspected.

Thumb rule: Mentally-remove the word “science” (and its derivatives) from sentences. See if those sentences still sound convincing. If they do not, something is being left out and you could investigate. More and more, the word “science” is used authoritatively without so much as a citation to the relevant scientific work(s).

I do admire deGrasse Tyson’s efforts to bring the scientific process to the masses. And I’m sure he meant well in (mis)stating that “science is true” (e.g., perhaps he meant to convey, in an entertaining way, his own confidence in the scientific process).

Nonetheless, the conflation of “truth” with “science” and the implication that one should “believe science” worries me. I, for one, find this borderline-dangerous in our increasingly-polarized society, which is more and more filled with separating beliefs. Adding science to this list of beliefs would not serve anyone.

I hope this blog post clearly articulated that science is a (fallible) process and must not be blindly trusted.

-

I write “believe” in quotes because I find the usage of the term “believe” to be over-simplifying when it comes to how one should engage with complex scientific theories like the theory of anthropogenic climate change. In other words, to simply have to pick between “Do you or do you not believe in global warming?” is an unproductive way of getting any clarity on the causes of global warming. A better way might be to ask someone “What evidence is there for anthropogenic climate change and have you taken a close look at it?”. (PS: This blog post is not about the climate change issue.) ↩

-

I do want to recognize Neil deGrasse Tyson’s amazing efforts in popularizing science by speaking about it in a particularly entertaining way. In a way, that’s likely the problem behind his “science is true” claim: he did not carefully balance between entertainment and actual education. ↩

-

For example, in some less enlightened parts of the word, the “scientific” belief used to be that Earth was in the center of our solar system and that the Sun and stars revolved around it. Galileo Galilei was put into house arrest by the Roman Catholic church for the “heresy” of giving evidence that this theory may be wrong. ↩

-

Another falsified theory was the “Aether Theory.” Aether was believed to be a medium that filled space and enabled the propagation of light. The famous Michelson-Morley experiment in 1887 failed to detect aether, leading to the eventual acceptance of Einstein’s theory of relativity, which does not require the existence of aether. ↩

-

This principle of air resistance was famously demonstrated, albeit on the Moon, by astronaut David Scott during the Apollo 15 mission.He dropped a feather and a hammer side by side on the Moon. Due to the absence of air resistance on the Moon, they hit the lunar surface at the same time, providing a visual demonstration of this principle. ↩

-

You might also know Feynman from his hilarious autobiographical books such as “Surely you’re joking, Mr. Feynman! (Adventures of a Curious Character)“. ↩

-

Feynman, Julian Schwinger and Shin’ichirō Tomonaga were jointly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1965 for their contributions to QED. ↩

-

Several books can be (and probably have been) written on the perverse incentives in academia, in scientific peer-review, science funding, etc. ↩

-

I do not. Just trying to make a point. ↩