tl;dr: …because (1) they are only secure when the tree is correctly-computed (e.g., secure with BFT consensus, but insecure in single-server transparency logs), (2) you cannot efficiently insert or delete leaves, and (3) they have worse proof sizes. What does that mean? Never implement one. Stick to Merkle tries (a.k.a., Merkle prefix trees). Or, if you are a masochist and like to deal with rotations, stick to balanced binary search trees.

$$ \def\Adv{\mathcal{A}} \def\Badv{\mathcal{B}} \def\vect#1{\mathbf{#1}} $$

Problem statement

Non-membership proofs in Merkle trees are surprisingly elusive to many people. The problem statement is very simple:

Suppose you have a server who wants to authenticate elements of a set $S$ to a client without ever sending the whole set to this client.

(For simplicity, let’s assume this is a set of numbers.)

Specifically, the server first computes a succinct authentication digest of the set, denoted by $d$, and sends $d$ to the client.

Then, the server is able to prove either membership or non-membership of an element in the set by sending a succinct proof to the client which the client can efficiently verify with respect to the digest $d$.

Design a Merkle tree-based solution for this problem.

The most popular solution to this problem seems to be to build a Merkle tree whose leaves are sorted. This, unfortunately, is a rather sub-optimal solution, both from a security and a complexity point of view.

In this blog post, I hope to dispel the myth of the effectiveness of this sorted-leaves Merkle tree scheme.

Warm-up: proving membership in Merkle trees

Recall that it, if we only need to prove membership, it is very easy to solve the problem by building a Merkle tree over all elements in the set and letting the digest be the Merkle root.

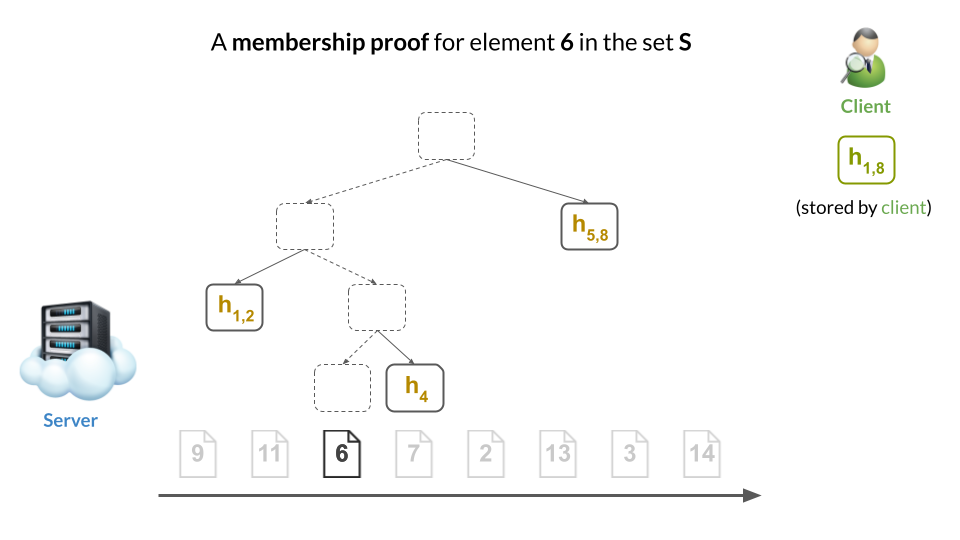

For example, here’s how this would look for a particular choice of set $S$. (Original slides here.)

Then, a membership proof would be a Merkle sibling path to the proved element’s leaf (i.e., the nodes in yellow):

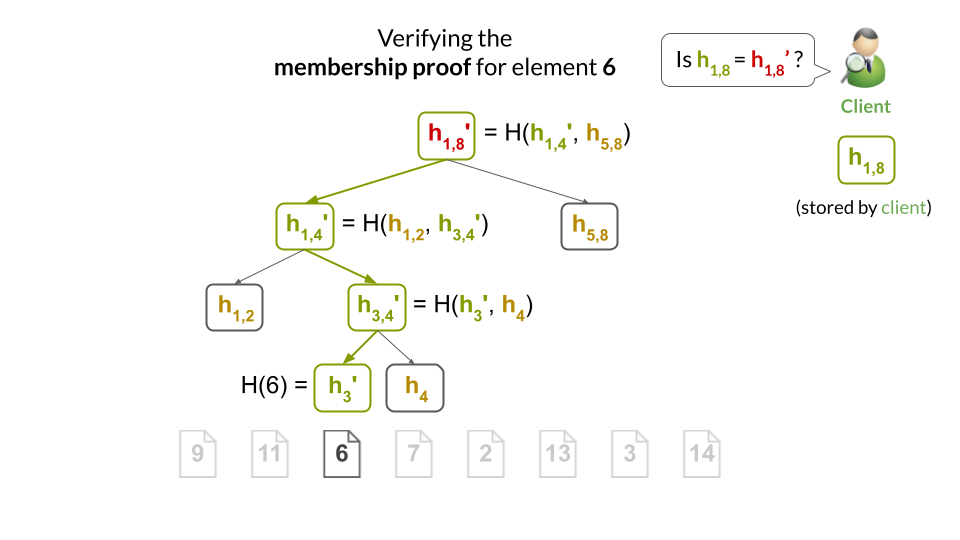

The client can easily verify the proof by computing the hashes along the path from the leaf to the root, and checking that it obtains the same root hash as it has stored locally:

Sort the leaves to add support for non-membership?

It seems that many people believe sorting the leaves is the right approach to enable non-membership proofs.

This blog post will argue, from three different perspectives, why this is a sub-optimal choice.

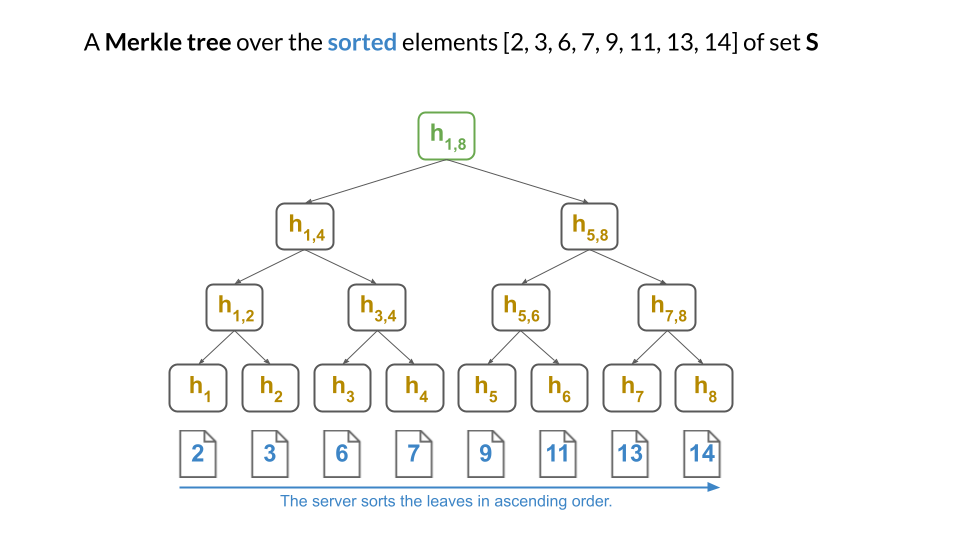

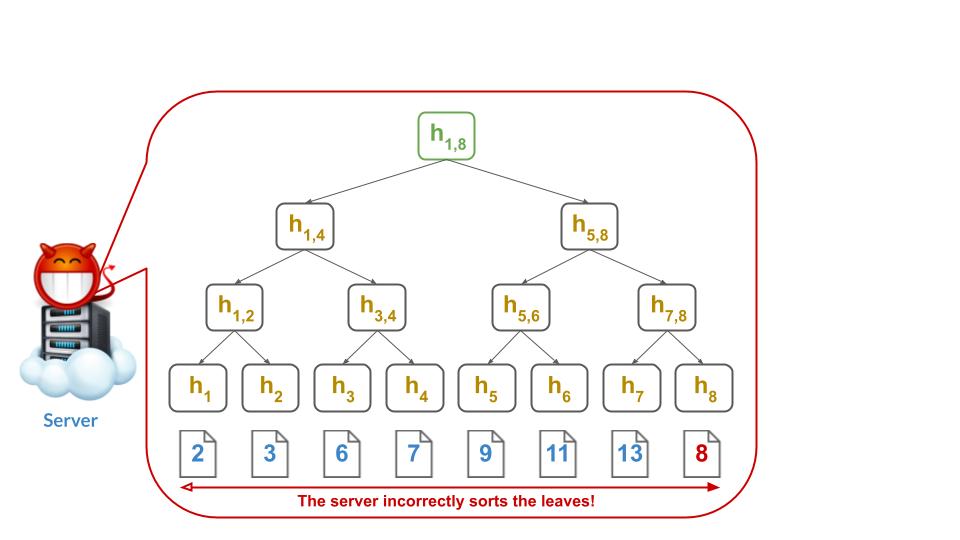

Okay! Let say that, instead of the solution from above, the server does indeed first sort the set $S$ as $[2, 3, 6, 7, 9, 11, 13, 14]$ and then computes the Merkle tree:

Clearly, the server can still prove membership as before: just give a Merkle sibling path to the proved element’s leaf.

But, now, it is also possible to prove non-membership of an element.

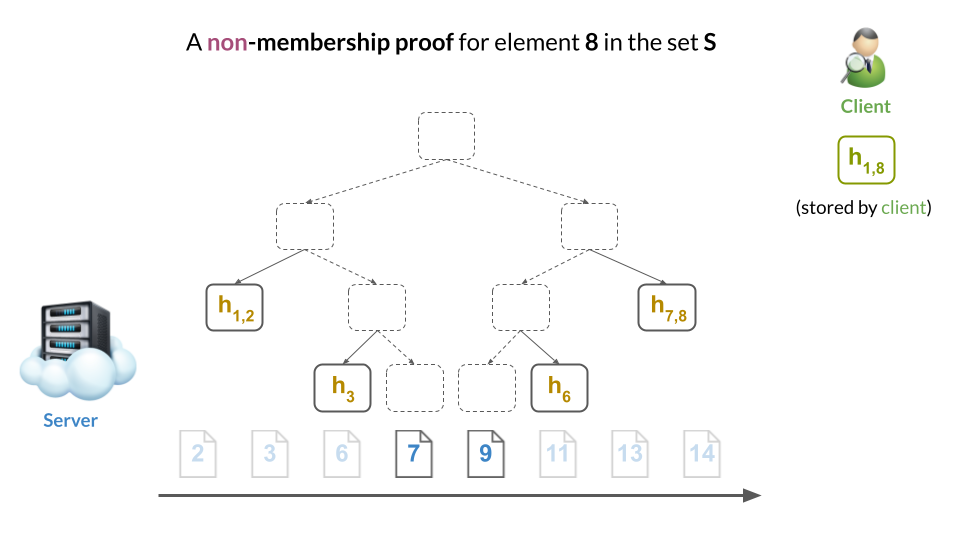

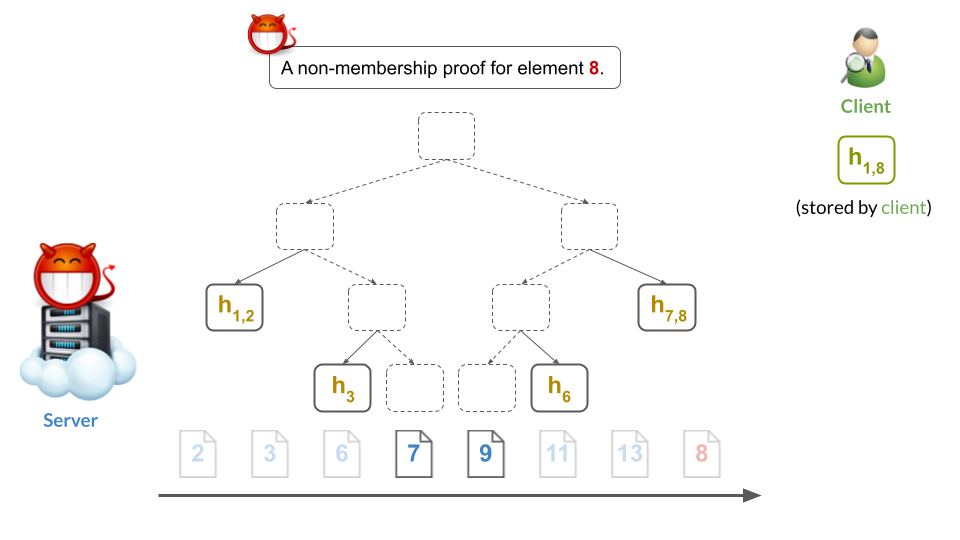

For example, we can prove non-membership of $8$ by showing that (a) both $7$ and $9$ are in the tree and (b) that they are adjacent. This implies there’s no room where 8 could fit. Therefore, 8 cannot be in the tree:

In other words, the two membership proofs for the adjacent leaves of $7$ and $9$ constitute a non-membership proof for 8, which would have to be placed between them (but cannot be since “there’s no room”).

Problem 1: Security

Can you spot the security issue? It’s a bit subtle and many people miss it…

Here it is: this scheme is secure only if the server correctly computes the Merkle tree over the sorted leaves.

Otherwise, if the server is malicious, it can re-order the leaves and pretend than an element $e$ is both in the set and not in the set.

For example, the malicious server could compute the tree as follows:

Note that the malicious server left 7 adjacent to 9, so that it can still give what appears to be a valid non-membership proof for 8:

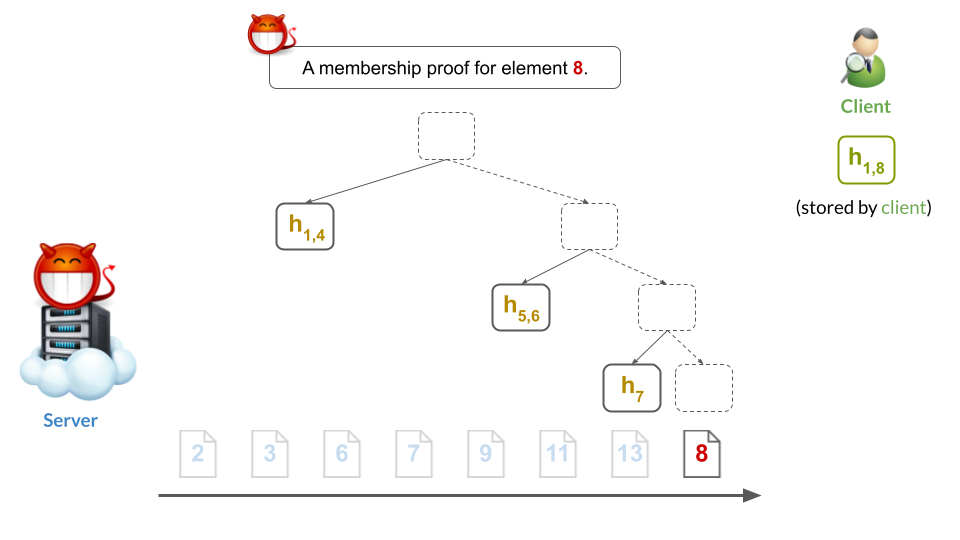

At the same time, note that the malicious server inserted a leaf for 8 somewhere else. As a result, the server can still give what appears to be a valid membership proof for 8:

This, of course, is very bad: the server was able to prove two inconsistent statements about the membership of 8 in the digested set. Put differently, it clearly cannot be that 8 is both in $S$ and not in $S$ at the same time. Therefore, the sorted-leaves Merkle tree is insecure when the server cannot be trusted to produce correct digests (and we’ll define security below).

In other words, this type of attack completely ruins security: it makes any proof meaningless to the client (e.g., proof that $8\in S$), since it could easily be followed by a contradicting proof (e.g., a contradicting proof that $8\notin S$).

When would the sorted-leaves Merkle tree be secure?

Not all hope is lost. In some settings, it can be reasonable to assume the digest (i.e., Merkle root) was produced correctly.

For example, in distributed consensus settings (a.k.a., in “blockchains”), there is no single server that dictates what the Merkle root of the data is. Instead, all $n = 3f+1$ servers try to compute the same correct root and vote on it. Servers who deviate from the correct root are ignored and consensus is reached on the correct one by a subset of $2f+1$ honest servers.

Therefore, in this setting, it is okay to rely on the sorted-leaves Merkle tree construction. (I’ll still argue here and here why you shouldn’t, but from different perspectives.)

Other harmless settings include single-client data outsourcing, where a client sorts & Merkle hashes his own data correctly, and transfers everything but the Merkle root to a malicious server.

Since the client has computed the correct root on his own, the client can rely on the server’s (non)membership proofs.

One thing worth emphasizing is that ad-hoc fixes to the problem of a potentially-incorrect digest are not worth it, especially since one can get a construction that needs no fixing from, e.g., a Merkle trie. Specifically, it is not worth it to require the server to prove that it correctly sorted the leaves (e.g., via a SNARK). Also, it is not worth it to rely on fraud proofs when one can have provably-correct behavior all the time. Lastly, it is not worth it to probabilistically audit the data structure to see if you can find two incorrectly-sorted leaves. None of these approaches are worth it because there exist more secure Merkle tree constructions like Merkle tries. Plus, these constructions are easier to update and have smaller proof sizes!

(Non)membership soundness definitions

We can formalize the setting in which authenticated set constructions (like the sorted-leaves Merkle tree) are secure.

Specifically, we can define a notion of weak (non)membership soundness that captures the idea that the malicious server must compute the digest correctly:

An authenticated set scheme has weak (non)membership soundness if for all (polynomial-time) adversaries $A$, the probability that $A$ outputs a set $S$, an element $e$, and two proofs $\pi$ & $\pi’$ such that, letting $d$ be the (correct) digest of $S$, $\pi$ verifies as a valid membership proof for $e$ (w.r.t. $d$) while $\pi’$ also verifies as a valid non-membership proof for $e$ (w.r.t. $d$), is negligible in the security parameter of the scheme.

Notice that the adversary outputs a set of elements from which the correct digest $d$ is computed.

In fact, there is a long line of academic literature on 2-party and 3-party authenticated data structures that rely on this type of weaker soundness definitions (see Papamanthou’s PhD thesis1 for a survey).

Unfortunately, many applications today inherently rely on untrusted publishers who can compute malicious digests of their data.

For example, in key transparency logs such as Certificate Transparency (CT), log servers can present any digest to new clients joining the system. Therefore, in this setting, authenticated data structures (whether sets or not), must satisfy a stronger notion of security which allows the adversary to construct the digest maliciously.

In fact, such a stronger notion simply requires that the adversary output the digest $d$ directly, which gives the adversary freedom to construct an incorrect one as in our attack above:

An authenticated set scheme has strong (non)membership soundness if for all (polynomial-time) adversaries $A$, the probability that $A$ outputs a digest $d$, an element $e$, and two proofs $\pi$ & $\pi’$ such that $\pi$ verifies as a valid membership proof for $e$ (w.r.t. $d$) while $\pi’$ also verifies as a valid non-membership proof for $e$ (w.r.t. $d$), is negligible in the security parameter of the scheme.

The moral of the story is to pick a Merkle construction that has this stronger notion of security, unless you are sure that your setting allows for the weaker notion and you stand to benefit from relaxing the security (e.g., perhaps because you get a faster construction). A good example of this is the KZG-based authenticated dictionary from Ethereum Research2 which has weak soundness (as would be defined for dictionaries), but that’s okay since their consensus setting can accommodate it.

Problem 2: Insertions and deletions

This one is much easier to explain.

Imagine you want to add a new element in your sorted-leaves Merkle tree of size 8.

What if it is smaller than everything else and has to be inserted as the first leaf of the tree?

Then, you would have to completely rehash the entire tree to incorporate this new leaf! This would take $O(n)$ work in a tree of $n$ leaves.

The same problem arises if you’d like to remove the first leaf.

To deal with the slowness of insertions, one can take an amortized approach and maintain a forest of sorted-leaves Merkle trees, where (1) new leaves are appended to the right of the forest as their own size-1 trees and (2) trees of the same size $2^i$ for any $i \ge 0$ get “merged” together by merge-sorting their leaves and rehashing. One can show this approach has $O(\log{n})$ amortized insertion cost. However, such amortized approaches still suffer from $O(n)$ worst-case times and must be de-amortized to bring the worst-case cost down to the amortized cost3.

On the other hand, dealing with deletions can be easier. Specifically, if you do not care about wasted space, then deletions can be done faster by simply marking the leaf as “removed” and trying to garbage-collect as many empty subtrees as you can. Nonetheless, in the worst case, the storage complexity of an $n$-leaf Merkle tree after $O(n)$ deletes remains $O(n)$ (e.g., imagine deleting every even-numbered leaf).

Problem 3: Proof size is sub-optimal

The other problem with the sorted leaves construction is that two Merkle paths must be given as a non-membership proof.

In the best-case, this can be exactly $\log{n}-1$ hashes, but in the worst case this can be as much as $2\log{n}-2$ hashes (e.g., when one proof is in the left subtree and the other proof is in the right subtree).

This is not so great if proof size is a concern. It is also not so great when the Merkle tree is stored on disk since it can double the proof reading I/O cost.

Furthermore, actually achieving the best-case proof size complexity in an implementation can be tricky: the developer must efficiently batch the fetching of the two Merkle proofs from disk or memory, taking care never to fetch the same sibling hash twice (or waste I/O).

If you really MUST sort your leaves…

…and you want to maintain strong (non)membership soundness, then there is a simple way to fix your construction.

All you have to do is store, inside each internal node of your tree, the minimum and maximum element in that node’s subtree.

Now, a Merkle proof, whether for membership or not, has to additionally reveal the minimum and maximum’s along the proven path. Importantly, when hashing up to verify the Merkle proof, the verifier must ensure the revealed leaf and all min/max pairs revealed are consistent and hashed correctly as part of the verification.

This will of course further increase the proof size of your construction. It will also increase the complexity of implementing the verification procedure, since the min/max ranges have to be incorporated into the hashing and one must check that, for all revealed ranges in the proof, a parent’s range encompasses their child’s range.

Feel free to consider this approach. You could try reproducing the attack from above. You’ll see that while you can present one proof, you’ll have difficulty presenting the other because you will not be able to forge the authenticated min/max ranges. Thus, this construction has strong (non)membership soundness.

Probably use a Merkle trie

This deserves its own post, but here are the key reasons you should probably use a Merkle trie:

- Tries over $n$ elements have height $O(\log{n})$, assuming you compress tree paths, which you can! For example, see the CONIKS line of work4.

- Tries are an intuitive data structure

- Tries do not require rotations to keep the tree well-balanced

- Merkle tries offer strong (non)membership soundness

- Merkle tries are relatively-easy to implement

There are of course some disadvantages too, but I find them negligible:

- Tries require a bit more hash computations to determine the path of an element in the tree (during insertion, updates, proof verification, etc.)

- Tries have some tricky edge-cases when implementing (e.g., inserting two elements whose first $k$ bits collide in an empty trie)

- Tries have some tricky edge-cases for proving non-membership

- e.g., when proving non-membership of $e$, either a leaf exists along $e$’s path but it’s for the wrong element, or no leaf exists at all

- This edge case arises in the simplest implementation of tries, which do not ensure the tree is full (i.e., fullness means every node other than the leaves has two children)

- Tries are vulnerable to adversarial insertions: an adversary can search for a key whose insertion depth will be very large

- However, to achieve depth $k$, the adversary will have to compute $2^k$ hashes, which gets expensive quickly.

In fact, some folks argue that the best trie implementation is via critbit trees5. Unfortunately, I do not know enough about their benefits, especially when Merkleized, but this is probably very much worth exploring.

History of non-membership proofs

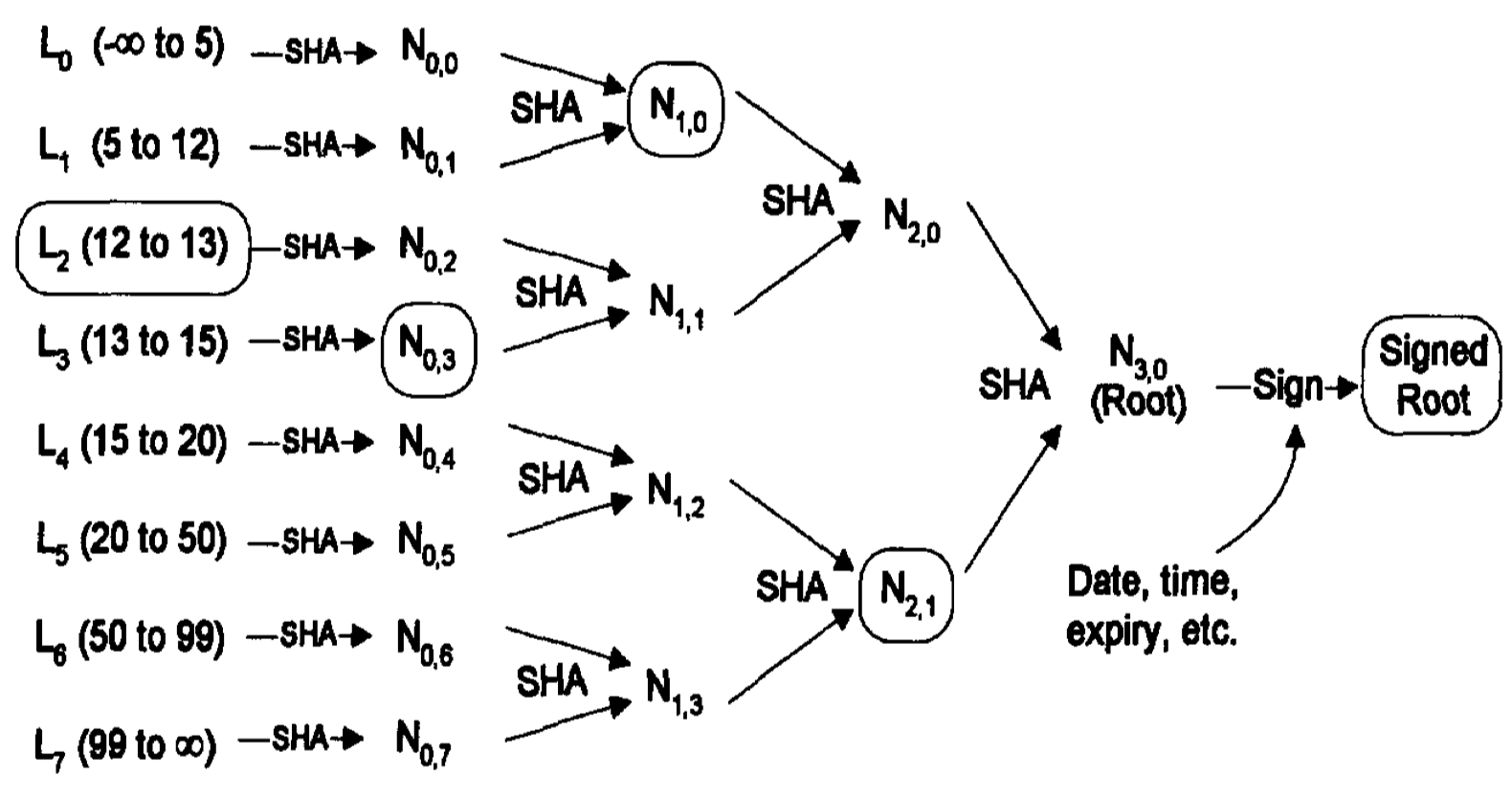

Kocher6 proves non-revocation of certificates via a sorted-leaves-like approach. His approach Merkelizes a list of sorted, non-revoked certificate ID ranges. Specifically, each leaf is a pair $(a, c)$ that says $a$ has been revoked but all certificates $b$ such that $b > a$ and $b < c$ have not been revoked.

Thus, one can prove non-revocation of $b$ by revealing the leaf $(a, c)$ that encompasses the non-revoked ID $b \in (a, c)$. One can also prove revocation of $a$ by revealing the leaf $(a, c)$.

A depiction of the sorted-leaves-like approach from Kocher’s original paper7. The set of elements being authenticated here (i.e., revoked certificates) is $S = \{5, 12, 13, 15, 20, 50, 99\}$.

Of course, Kocher’s approach is vulnerable to the same mis-ordering attack we discussed above. (Furthermore, it also suffers from inefficiency of updates.)

Indeed, Buldas et al.7 point out the mis-ordering attack and solve the problem by Merkelizing a binary search tree (BST) instead, which they baptize as an authenticated search tree. However, as far as I could tell, the paper does not describe how to efficiently update such authenticated search trees while keeping them balanced (i.e., solve problem 2).

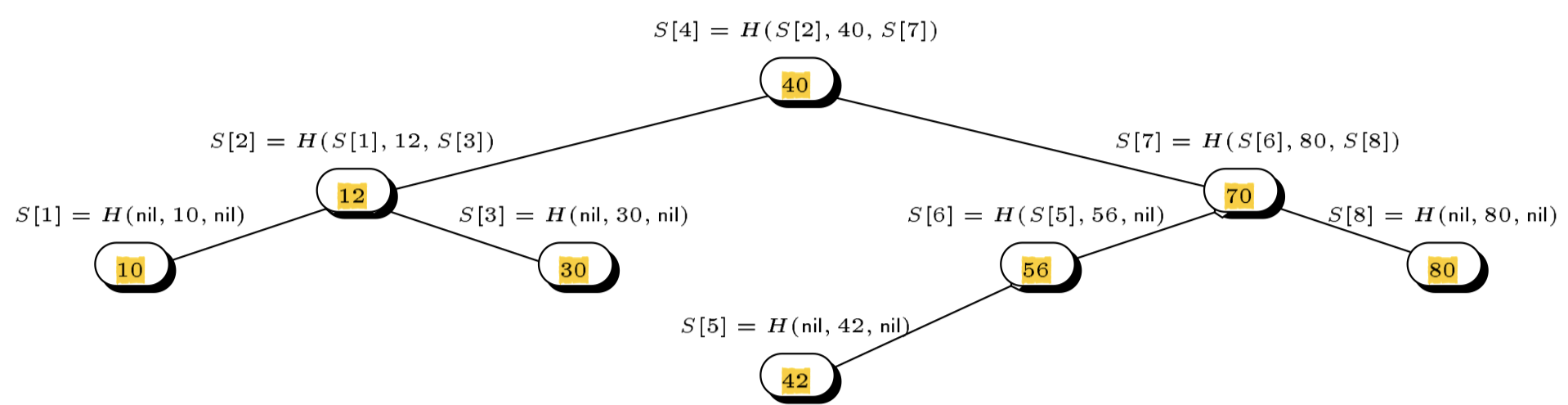

A depiction of the authenticated (binary) search tree approach from Buldas et al.’s original paper7. The set of elements being authenticated here is $S = \{10, 12, 30, 40, 42, 56, 70, 80\}$.

Fortunately, a few years earlier, Naor and Nissim8 had proposed an authenticated 2-3 tree construction which did solve the problem of efficient updates, addressing all problems highlighted in this post. Surprisingly, Naor and Nissim did not point out the mis-ordering attack on Kocher’s work, only the inefficiency of updating it. Also surprisingly, there are no pictures of trees in their paper :(

I still find Merkle tries much easier to implement, but I never tried implementing a 2-3 tree.

Conclusion

Hopefully, this post gave you enough context on the problems of this popular sorted-leaves Merkle tree construction.

This leaves me wondering: are there any advantages to sorted-leaves Merkle trees?

The only advantage I see is that MHTs with sorted leaves are easy to describe: just sort the leaves, Merkleize them and prove non-membership of an element $e$ by revealing the two paths to the adjacent leaves that exclude $e$.

However, just because they are easy to describe does not mean they are easy to understand.

At least, from the questions and answers I see online, and from conversations with researchers and other engineers, their security caveats are not well understood.

First, my own answer on StackExchange makes an unfortunate use of the “sorted Merkle tree” terminology to refer to either a binary search tree9, a trie, or a Sparse Merkle tree (SMT), which actually all have strong (non)membership soundness. Even worse, tries and SMTs are not really sorted, since data is typically hashed before being mapped into the trie.

Another StackExchange answer seems to perpetuate the myth that all you need for non-membership security is to sort the leaves, without paying attention to the weak (non)membership soundness guarantees of such a construction.

The answer quotes this post, where a sorted-leaves Merkle tree solution is described to solve a non-membership problem like the one in the intro. Unfortunately, the answer discards the nuance of the quoted post: there, the original author realized that the leaves could be incorrectly-sorted & resorted to fraud proofs to catch such misbehaviour; i.e., if someone detects a mis-ordered tree, they can easily prove it with two Merkle paths to the out-of-order leaves.

Yet a much easier and cheaper solution would have been to use an authenticated set with strong (non)membership soundness as defined above (e.g., a Merkle trie). This would have simplified the higher-level protocol, since it would have removed the need for fraud proofs, which are clearly less desirable when one can have provably-correct behavior all the time.

Oh well, we live and learn. Don’t sort your Merkle tree’s leaves, okay? Use a Merkle trie.

And, if you somehow find a reason to sort your leaves, please let me know what were the advantages of doing it. Don’t forget to compare to more secure solutions such as Merkle tries, which have strong (non)membership soundness.

-

Cryptography for Efficiency: New Directions in Authenticated Data Structures, by Charalampos Papamanthou, 2011, [URL] ↩

-

Multi-layer hashmaps for state storage, by Dankrad Feist, 2020, [URL] ↩

-

Static-to-dynamic tranformations, by Jeff Erickson, 2015, [URL] ↩

-

CONIKS: Bringing Key Transparency to End Users, by Marcela S. Melara and Aaron Blankstein and Joseph Bonneau and Edward W. Felten and Michael J. Freedman, in {24th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 15)}, 2015, [URL] ↩

-

Shoutout to Alnoki, the cofounder of Econia Labs who brought crit-bit trees to my attention. ↩

-

On certificate revocation and validation, by Kocher, Paul C., in Financial Cryptography, 1998 ↩

-

Accountable certificate management using undeniable attestations, by Ahto Buldas and Peeter Laud and Helger Lipmaa, in ACM CCS’00, 2000, [URL] ↩ ↩2 ↩3

-

Certificate Revocation and Certificate Update, by Moni Naor and Kobbi Nissim, in 7th USENIX Security Symposium (USENIX Security 98), 1998, [URL] ↩

-

Note that a binary-search tree (BST) is a tree where all left descendants of a node are smaller than that node & all right descendants of a node are greater than that node. Importantly, trees with sorted leaves are not conceptualized as binary search trees, since their data is stored in the leaves, not in the internal nodes. ↩